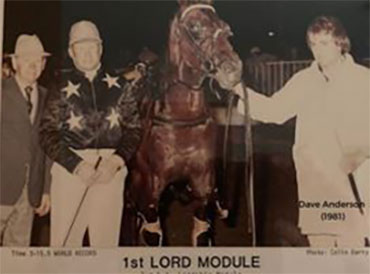

It’s 40 years to the day since Lord Module last raced. Not that anyone at the time knew it was his final race. So to mark the occasion who better to talk to than two key figures on that day in 1981.

by Dave Di Somma, Harness News Desk

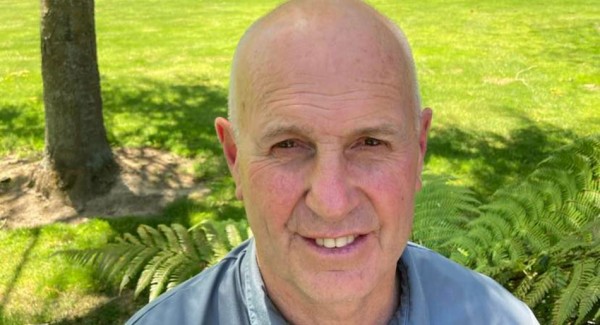

“Very disturbing” was the reaction by Dave Anderson to the fact that it’s been now four decades since Lord Module last raced.

Anderson was the strapper in charge of the mighty pacer that night at Addington on November 21 1981.

Driven by Jack Smolenski, Lord Module went from last at the 300 to topple a field that included other greats like Gammalite, Armalight, Hands Down and Bonnie’s Chance in the Group Two Allan Matson Free For All.

It’s turned into harness racing folklore.

“It’s hard to believe it was so long ago,” says Anderson, who also trained over 160 winners from 1989 to 2015, “it’s very disturbing!”

“And I remember the thrill of it all, the crescendo of sound – I’ve never experienced anything else like it, everyone went wild.”

No-one had a better view of the epic encounter than commentating legend Reon Murtha. Over the years he’s said it was the most emotional moment in his nearly half century of race calling though he also remembers it for another reason.

“I was given the wrong sectionals during the race and I thought that can’t be right, and I got confused. People said it was a great call but my brain was scrambled!”

This wasn’t a case merely of a great horse performing against and beating the best – there were so many more elements to it than that.

Lord Module had a reputation as a rogue – even described as “having the mental capacity of an errant three-year-old with a toothache.”

Having bad quarter cracks, which caused him a lot of torment throughout his career, didn’t help his temperament. He was known to flop down on the track for no apparent reason and you didn’t want to get on the wrong side of him.

“He was bloody difficult,” says Anderson, “he once bit the thumb off one of his handlers! You always had to be very careful around him.”

His manners – both at standing starts and behind the mobile gate – were appalling too and many times he famously lost a lot of territory (upwards of 60 metres) only to prevail from seemingly hopeless positions. At a time when harness racing was in its heyday Lord Module was a star – and he had a devoted fan base.

The great Cecil Devine, a classic old school trainer originally from Tasmania, bought the son of Lordship for $3000 at the National Sale. He would go on to win 28 of 93 races, including the 1979 New Zealand Cup, and earn around $240,000.

Devine trained the horse throughout but had to hand over the reins when he got to 65, the compulsory retirement age at the time.

In 1981 Lord Module was banned for a time from racing because of his unruly behaviour and even before the Allan Matson it wasn’t even guaranteed that he would get clearance to start. The stipes had warned Devine that their patience was wearing thin.

On that day 40 years ago he started 3/5 in the betting. Armalight was the favourite.

At the start all eyes were on Lord Module – would he start? Or would it be another debacle?

With Devine watching on from the stands Lord Module looked to be up to his old tricks and “pig-rooted” from the mobile, only for Smolenski to quickly bring him into line. As they say – the crowd went wild.

Lord Module was last on the fence with a lap to go and at the 300 he made his move, six wide!

The champion just keep trucking.

“Oh, he’s putting in a brilliant run down the outside,” exclaimed Murtha as Lord Module reeled in them to win by a length.

“They won’t stop clapping this side of next week,” he said as he announced the winning time, 3:15.5 for the 2600 metres, a mile rate of 2:00.9.

A hero’s welcome doesn’t quite sum up what happened next.

“It was a great way to finish,” says Anderson, “people were jumping over seats – the din, the swaying of the stands, and people screaming at the tops of their voices …. it’s a good memory.”

Recurring problems with quarter cracks meant Lord Module never raced again. His retirement announced just a few months later. He died in 1997.

“He was in the top five in my era,” says Murtha, ” he overcame the impossible and he was a great favourite with the crowds.”

USA

USA Canada

Canada Australia

Australia New Zealand

New Zealand Europe

Europe UK / IRE

UK / IRE