The following article is a two-part series on the fate of racing in the state of Illinois. Part two of the series will run on Harnesslink Wednesday.

Illinois horse racing has fallen from grace. The once fruitful state that offered so many excellent racing opportunities for both harness racing Standardbreds and Thoroughbreds is now nothing more than a pitiful shadow of the racing’s glory days that flourished throughout the Prairie State.

While a number of factors contributed to this demise—both socioeconomic and political—by examining said factors, a common thread emerges that can be seen in other, seemingly healthy racing states, and bodes as a stern warning to those in charge to closely examine the warning signs within their own racing communities.

While a number of factors contributed to this demise—both socioeconomic and political—by examining said factors, a common thread emerges that can be seen in other, seemingly healthy racing states, and bodes as a stern warning to those in charge to closely examine the warning signs within their own racing communities.

Beginning at the turn of the 20th Century, horse racing had been one of the main revenue producers for Illinois—closely tied to the agricultural aspects of the Prairie State—with both the runners and harness horses drawing huge crowds at not only pari-mutuel tracks, but the numerous county fair tracks that dotted the Midwestern landscape as well.

Horseracing constitutes the oldest form of legalized gambling in Illinois, and prior to 1984, fans could place a wager only on-track, at a pari-mutuel facility.

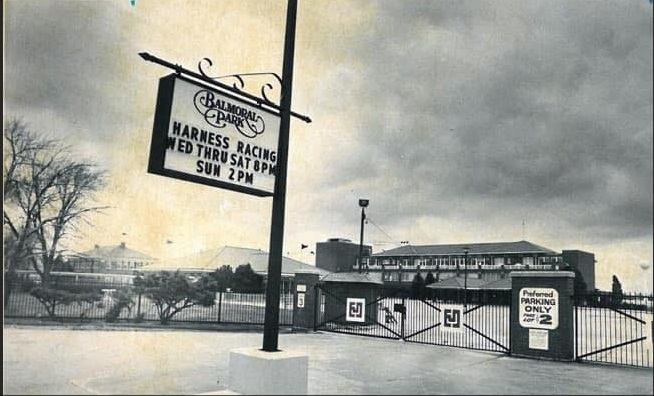

Numerous tracks had sprung up as early as the 1840s—such now defunct venues as Brighton Park Trotting Park (which later morphed into the Chicago Stockyards), Dexter Park, the Chicago Driving Park, Libertyville, Lake Forest, and the Austin Driving Park located in the heart of Chicago. Those existed well before Hawthorne opened its doors in 1891, followed by Lincoln Fields/Balmoral (1926), Arlington Park (1927), Maywood (1946), and Sportsman’s Park (1932). Pari-mutuel wagering on racing was first legalized in 1927, then outlawed, before being legalized again in 1946 in Illinois.

What followed was more than half a century of the best harness racing in North America at Chicago area ovals, where some of the finest horseflesh in history graced those surfaces. One of the best years was 1979, when an average 13,136 fans came out to Sportsman’s Park on a nightly basis during their 99-night meeting, wagering more than $1.6 nightly. The Cicero-based five-eighths mile oval had made its debut 30 years earlier, on July 18, 1949, when 11,789 patrons wagered $237,812—the highest totals ever for a North American racetrack on opening night.

Sportsman’s Park had been the pinnacle of Illinois harness racing—headed by the powerful Johnston family. William Johnston, Sr., was president of the National Jockey Club (NJC) when Sportsman’s was a Thoroughbred-only venue in 1947, and 20 years later Johnston, Sr., turned over the reins to his son, Billy, Jr., when he retired. Stormy Bidwell took over the Thoroughbred side of the operation, while Billy, Jr., focused on the harness racing side as president of both the Chicago Downs and Fox Valley meets. Johnson, Sr., had brought an after-dark harness racing product to the public long before there were evening ballgames or any other sporting event—making Sportsman’s Park the premiere playground for nighttime entertainment.

But by 1984, Illinois racetrack owners had noticed a shift—their patrons were not attending in throngs as they had in past seasons. While attendance was still hefty for events including the American Nationals, the Maywood Pace, and the World Trotting Derby, wagering had been in decline since the late 1970s.

Then, in the Spring of 1984, Sportsman’s Park introduced Intertrack Wagering (ITW), and this new era of electronic wagering, which allowed patrons to wager on the satellite transmission of live racing from a host track within Illinois, to the track where the patrons were located, became known simply as “Intertrack.” Prevailing thoughts among racetrack owners were that this would help to reverse the downward trend in declining wagering dollars.

Arlington Park followed by supporting Intertrack during its 1984 summer meet. Joseph Joyce, Arlington president and chief executive officer at the time was quoted in an April 24, 1984, United Press International (UPI) feature that, “Based on intertrack experience at Sportsman’s Park this Spring, we expect and accept that there will be revenue losses because of losses in attendance and handle. But if the losses exceed what we anticipate, we reserve the right to discontinue the program.”

Sportsman’s handle and concession sales declined as a result of Intertrack by 20%, but the boost in Intertrack wagering helped produce some of the biggest purses at the Cicero track that year. In that same UPI article, Joyce added that, “Arlington’s new ownership (Dick Duchossois, Ralph Ross, Joe Joyce, Sheldon Robbins) is dedicated to improving the quality of racing at Arlington Park, and we recognize that Intertrack wagering will increase the purse money we can offer to attract better horses.”

One year later, Sportsman’s Park reaped further benefits of Intertrack, by cashing in on the Arlington Million, won by Teleprompter, during what was coined “The Miracle Million,” after the devastating fire on July 31 which leveled the grandstand. Some 8,217 fans showed up at Sportsman’s to bet the Million, while another 3,127 were on track at Maywood to bet the nation’s richest Thoroughbred event.

As well, according to a Feb. 12, 1985, Chicago Tribune article, “Arlington and Maywood are currently accepting wagers on Hawthorne’s harness meet during the afternoon programs, and it’s been a big success, especially on Saturdays. Arlington pumped $292,667 through the mutuel windows…and Maywood added $207,654 as Hawthorne barely missed a rare $2 million day with $1,931,729.”

“The main thing is that people are here and they’re happy,” said Sportsman’s president Billy Johnston in an Aug. 26, 1985, Chicago Tribune feature. “If they’re interested in racing, in the long run we’ll get them.”

In July of 1987, the first off-track betting parlors were legalized in Illinois—first at Peoria in September and later in November at Rockford. At the time, the state’s seven tracks were granted two parlors each to own and operate. It was also during this time that the Steinbrenner family became involved in Illinois racing—purchasing a slice of the Balmoral pie and expanding harness racing at the Crete facility to five days a week. The horsemen had missed an opportunity to grab a healthy share of the OTB splits, and were left with a 25/75% deal, providing a trivial sum to the purses.

While Intertrack boosted the dollars being wagered on the Illinois racing product, on-track attendance continued to steadily decline. A March 14, 1988, Chicago Tribune article reported that, “Despite the addition of 13 programs, on-track betting at the (Hawthorne) meeting declined two percent and attendance was down one percent. But Intertrack and off-track betting came to the rescue…with a combined average of 6,489 customers (who) sent a daily average of $1,161,885 through the mutuel machines. Hawthorne’s on-track averages were 4,528 for attendance and $743,321 for handle.”

According to Illinois Racing Board figures, on-track wagering was slightly above $800 million in 1984, but Intertrack helped push the total handle to slightly more than one billion dollars, and by 1990, those figures had jumped to well past $1.2 billion, with the combined monies from Intertrack and the OTBs. Those figures remained above the $1.2 billion mark from 1990 through 1996, when the overall decline began again in Illinois.

The Illinois horse racing community did “miss the boat,” on several occasions, having had the chance to become involved in both the off-track betting parlors (OTBs) and the riverboat industry, where they might have grabbed a substantial chunk of change that could have sustained them and keep them afloat.

Businessman and horseman Bill McEnery, who was the IHHA president at the time, encouraged the horsemen to become involved in both segments of gambling expansion. This was a man who was no stranger to making a deal, but the horsemen would have had to have made a substantial financial investment into both opportunities, and they declined, despite McEnery’s encouragement.

In February 1990, Illinois became the second state to legalize riverboat casinos, with the passage of the Riverboat Gambling Act, authorizing ten riverboat casino licenses that allowed for each license to operate two riverboat casinos. The Alton Belle was the first to launch on Sept. 11, 1991, and since then, multiple changes have taken place to the wagering and tax rates, as well as the authorization of six new casino licenses, and racino licenses, via legislation passed in June 2019.

In the fall of 1991, Maywood, and its sister track Balmoral Park, began “dual simulcasting,” a format which allowed for the back-and-forth, alternative racing schedule at both tracks on the weekend evenings. Dual simulcasting had a strong following, lasting through 1997, and was only hindered when there was an on-track mishap or a time-hindering incident.

Then, on June 1, 1995, the Full Card Simulcasting Bill was enacted by the Illinois legislature, bringing with it the misconceived, misunderstood, and misrepresented notion of “recapture.” Within the law, which permitted full card simulcasting at all Illinois racetracks, was the “recapture clause, which established a 50-50 split from non-Illinois simulcast revenue between horsemen and the racetracks.

Then, on June 1, 1995, the Full Card Simulcasting Bill was enacted by the Illinois legislature, bringing with it the misconceived, misunderstood, and misrepresented notion of “recapture.” Within the law, which permitted full card simulcasting at all Illinois racetracks, was the “recapture clause, which established a 50-50 split from non-Illinois simulcast revenue between horsemen and the racetracks.

The clause mandated that if during one calendar year, the total dollar amount wagered on Illinois racing at all in-state locations, was less than 75% of the 1994 amount wagered, the racetracks were entitled to recapture two percent of that difference.

Some will recall that Sportsman’s Park held a mini press conference one afternoon in their grandstand that summer of 1995, with Director of Racing and future United States Trotting Association (USTA) President Phil Langley explaining what great legislation this was for the horsemen and how recapture would never kick in. It is highly likely Langley believed what he was telling the nearly 1,000 horsemen in attendance that day, for as someone who loved racing, he certainly was not wanting to see the purses decline as a result of the recapture clause in the manner they did.

Langley had another reason to be optimistic, as 1995 was the year that Illinois had the highest ever number of harness racing programs, with a combined total of 516 races between Hawthorne, Maywood, Balmoral, and Sportsman’s.

Illinois racing did initially appear strong the following season in 1996, when the Illinois Department of Agriculture initiated the Million Dollar Bonus—paid to any horse that could win stakes at Springfield, DuQuoin, and on Super Night. Koochie (Bolla), a 2-year-old trotting filly, owned, trained, and driven by JD Finn, took the $50,000 Illinois State Fair Filly Stakes at Springfield, the $45,000 Shawnee at DuQuoin, and the $106,000 Lady Lincoln Land at Sportsman’s Park’s Super Night to notch that prize.

However, the devastating results of recapture reared its ugly head at the end of 1996, mandating that the Illinois Standardbred horsemen had to pay the tracks $4,406,000: $1.6 million from Maywood; $1.3 million from Balmoral; $864,000 from Sportsman’s Park; and $642,000 from the Hawthorne purse accounts.

It was also during this time—the mid-1990s—that the Chicago newspapers stopped carrying the results and morning line handicapping odds from the Illinois tracks. Sportsman’s and Arlington continued to have race results phone lines that patrons could call into, but the days of full charts, handicapping picks, and regular racing stories in both the Chicago Tribune and Sun Times went the way of the Dodo.

Recapture continued to plague the horsemen, who were dealt another blow on Oct. 9, 1997, with the closure of Sportsman’s Park. No other harness track had the panache nor style of Sportsman’s, with its seven-eighth’s mile oval, and hairpin first turn onto Laramie Avenue. A year later, Arlington Park closed its doors temporarily. Thus, within a noticeably brief time span, Illinois had allowed its two finest racing venues to shut down–systematically devastating the horse racing communities of both breeds.

Part two of this article will appear on Wednesday.

by Kimberly Rinker, for Harnesslink

USA

USA Canada

Canada Australia

Australia New Zealand

New Zealand Europe

Europe UK / IRE

UK / IRE