This article is Nicholas Barnsdale’s thesis submission for his Bachelor of Journalism degree from Humber College. Nicholas has been involved in harness racing since childhood and completed his internship at Harnesslink. After hearing countless stories of the heyday of packed crowds at harness tracks, he wanted to investigate how and why the sport declined.

Since 1967, wagering on harness racing in Canada has fallen 78 per cent. In the United States, annual attendance sunk an identical amount from its peak in 1975 to the last available data point in 2005. Blue Bonnets Raceway in Montreal, Sportsman’s Park in Chicago, Greenwood Raceway in Toronto, and many others have closed forever, taking decades of memories and many livelihoods with them. Harness racing, once a cultural staple in the United States and Canada, is known primarily only to its lifers. Football, basketball, hockey, and soccer exploded in popularity while the people stopped coming to see the trotters and pacers.

But why? How did we get here? Where did everybody go?

Did the lottery and slots suck the gambling dollars out of an industry reliant on it? Have the multiplying options for entertainment drawn people away from the rail? Maybe the product of racing itself is simply not exceptionally appealing as a gambling or spectating prospect. Everyone who cares about standardbred racing has felt the pressure of the headlines that keep saying the industry is getting closer to the void. And most have considered why this once-beloved American and Canadian sport has been declining for decades.

Most of the industry’s participants have an opinion. Many have watched their life’s greatest passion become an afterthought in the public sphere. No two people have the same background, but there is a collective experience of witnessing the decline, especially among the sport’s more populous older demographic that has been involved with it throughout.

Steve Wolf’s journey began in the late 1970s when he and his father operated a stable out of Meadowlands Racetrack in New Jersey. Wolf then worked in publicity roles at Liberty Bell Park and Brandywine Raceway – neither of which now exist – and the Standardbred Breeders and Owners Association of New Jersey. Later, Wolf held executive roles at Freehold Raceway in New Jersey and Pompano Park in Florida, where he currently resides. The 66-year-old Flemington, N.J. native has won many awards for his media work and is a member of the United States Harness Racing Communicators Hall of Fame. He has seen most of the sport’s collapse in popularity and profitability. His home track of Pompano Park, following a political battle, met its demise in 2022 after 58 years of live racing.

“Oh, it’s very sad to think of what it was when I first got started in the business,” he said. “I mean, it’s very, very sad. It’s so difficult to look forward now to get a job in the industry today. I mean, I feel very fortunate that I got into the business when I did, but to also watch it decline and know some of the reasons why on an individual basis is sad. It’s just so sad because this was such an American sport.”

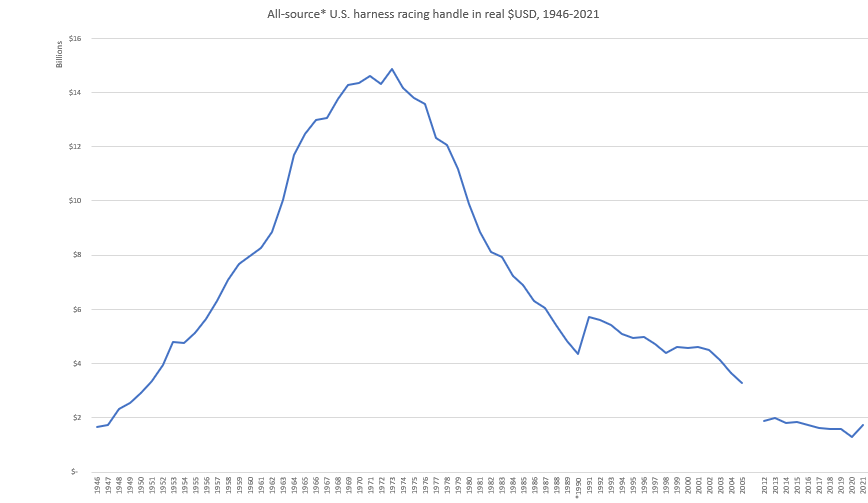

There are no published estimates for jobs created or lost in harness racing, but the industry employs many. Ontario Racing, an advocacy and organizational body for the sport in Ontario, estimates anywhere between 30,000 and 50,000 individuals work in horse racing overall in the province alone. The Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation, which operates the province’s gambling industry, estimates an economic impact of $1.88 billion from horse racing in 2018. It is an important industry, both to its participants and to its economic benefactors. But it’s nowhere near as prominent as it once was. The Canadian national harness racing handle, the amount which is wagered each year, crashed from an inflation-adjusted $2.28 billion in 1969 to $491 million in 2019. In the United States, handle in real dollars peaked at $14.85 billion in 1973; in 2021, Americans bet $1.72 billion. Attendance to harness racing fell from 7,612 per race day in 1965 to 1,600 in 2005. By the mid-1990s, most tracks had stopped publicizing rapidly receding attendance figures. It begs the question: where did everybody go?

United States and Canadian Hall of Fame driver Bill O’Donnell has a similar observation. Nicknamed Magic Man, O’Donnell began piloting harness horses in races in the mid-1970s but gained prominence when he moved to Saratoga Raceway in New York in 1979. He set a single season record for most wins by a driver at one track that season. He became a mainstay at The Meadowlands but drove in many of the sport’s greatest races at various tracks. In a career of more than four decades, he won more than 5,700 races.

“There was so many more people around [then],” he said. “Now, I’m talking about being in New Jersey. There was so many people that want to be involved in it. right? It was new, it was in an area, it was six miles from downtown New York, and there was Wall Street right there, right? A lot of the business guys, they all got involved in it. And [The Meadowlands) was the place to go. The restaurants were great. You know, we had Pegasus, it was full every night. We raced six nights a week. There’d be, you know, 12,000 people on a bad night. Twenty to 25,000 on a good night? I don’t know really. It lost its luster, put it that way. I don’t know why.”

There is such a complex web of related factors that nobody may ever be able to comprehensively explain why harness racing finds itself in its current situation. But there are many hypotheses. The most popular explanation is that other forms of gambling ended harness racing’s longstanding monopoly on wagering dollars. In Canada and most U.S. states, horse racing was the only way anyone could legally make a bet. Lotteries were banned in the United States in 1895 and did not return to the mainland until 1964, though states only began to introduce them in greater numbers in the 1970s. This is similarly applicable to casinos, though they were legalized earlier in states such as Nevada. Canada has a similar story: pari-mutuel gambling, the type employed by horse racing, was the only form of betting allowed from 1910 to 1970.

Wolf points to the loss of the gambling monopoly as a main reason for the industry’s decline. He believes that the introduction of the lottery was the first cut of many – an initial cut that harness racing made a lot worse by refusing to cooperate.

“(Up until the ’70s), there was no other places to make wagers, except for horse racing. And because of that, horse racing had, over the years, established itself as the place to go, you know, if you wanted to make wagers. […] But, in the 70s, states started coming up with the lotto,” Wolf said.

“So lotteries made it very simple, without the studying of race program, to make a wager. And as that became more and more popular, the onus on racing began to dwindle. And racing also never changed its style and never adapted to a lottery. At the time, it said to itself, ‘we don’t want to do anything, we don’t want to go to bed with this lottery business,’ you know, ‘we don’t want to share any profits or anything.’”

Among other things, O’Donnell assigns partial blame to the lottery as a contributor to the downfall.

“I think, well it would be the lottery coming in, right,” he said. “Not only a lottery – years ago, you bought a ticket, and it was just seven numbers or six numbers. Go to the store now – see how many things you can buy that are related to the lottery thing. It’s wild.”

Much of the overall horse racing industry cites the lotto as the first sign of trouble. Bennett Liebman, government lawyer in residence at Albany Law School and former New York Racing Association director, wrote in his New York Times blog in 2010 that “racing had a nearly total monopoly on gambling until the lottery came in. It may not be a coincidence that racing’s best year in New York was 1964, and we’ve been going downward since then.” He noted that it failed to gain a significant market share until the 1980s, but that “it provided the first form of convenience gambling, where you did not have to go to the track to make a bet.”

Steven Riess, who wrote several books on sport, organized crime, and horse racing, summarized in a 2014 work that “certainly the proliferation of state lotteries and their seductive promises of instant fortune hurt every phase of the gaming business.” Liebman estimates that pari-mutuels accounted for around three per cent of overall gambling in 2010.

Wolf argues that racetracks should’ve sought to incorporate the lottery as quickly as possible. “First thing it should have done was each state needed to make arrangements to work with the lottery companies hand-in-hand from the beginning,” he said.

But not everyone agrees that sweepstakes were a major factor for the people abandoning racetracks.

Roy Kaplan, in his paper The Effects of State Lotteries on the Pari-mutuel Industry, wrote that “to outward appearances, it would seem that the ascendancy of lotteries has come at the expense of the pari-mutuel industry, in particular horse racing. But outward appearances can be deceiving. For one thing, the decline in attendance and wagering has been broad and widespread, not confined to lottery states. For example, Kentucky was experiencing a decline before its lottery, as did many other states.” Kaplan explained in the piece that while Florida’s introduction of the lottery broke records, pari-mutual wagering only fell slightly, which can also be attributed to other factors of the time. Overall, Kaplan’s point was that “the lottery has probably had an adverse effect on the pari-mutuel industry in and outside of Florida, although it is not as drastic as generally suspected nor as significant as other factors.”

Some also point to other gambling-related factors, like the introduction of the casino and, more recently, online betting. The first United States casino outside of Nevada opened in Atlantic City in 1978. Canada was slightly later to the table with the first commercial casino opening in 1989. Recently, bettors in many states have gained access to online wagering websites which allow them to bet from their homes. These instant media are often seen as a direct threat to horse racing, an affair which typically entails 20 to 30 minutes of waiting between each one-to-two-minute race.

“(There’s) just more things for people to do,” O’Donnell said. “Games, you know what it’s like, especially with young people. They always, you know, a lot of them bet online on everything, right?”

Moira Fanning, the chief operating officer and publicity director of the New Jersey-based Hambletonian Society, agrees with the view that new forms of gambling kickstarted the downfall of standardbred racing.

“I think the general contraction can be attributed to losing the gambling monopoly,” she said. “Horse racing, with very rare exceptions, like the fairs or the Goshen, was the only way people could make legal bets. There wasn’t lotteries, there wasn’t casinos unless you specifically went to Monte Carlo or Vegas.”

Fanning became hooked on harness racing when she became a groom in the mid-1970s. She moved around to different stables in New Jersey, but she knew that harness racing was her calling.

“Once I went there and worked there, I was so enamored of them, that you could jog them and train them in a way that you couldn’t with thoroughbreds, too,” she said. “That to me was a huge part of their appeal.

“I, of course, love horses, love racing, but I really only like the racing part of it. I’ll go anywhere to see horses, but I don’t feel the same way as I do about horse racing about polo or barrel roping or dressage, or quarter horses or whatever. I just like horse racing.”

After working directly with her equine companions for several years, Fanning moved into the publicity department at Brandywine Raceway, which no longer exists. She then held a similar role at the also now-defunct Garden State Park before assuming a role at the Hambletonian Society, which administers harness racing’s most valuable races. She has now worked there for 38 years.

Fanning puts forward the idea that harness racing’s slow, quiet decline can also be seen in, and partially blamed upon, communities leaving behind the racetrack as a favoured way to spend a night.

“It was also one of the very few sources of affordable entertainment that people had,” she said. “I don’t know back in the in the 50s and 60s if they charged admission, but even if they did, it was still someplace you could spend a night, and it wouldn’t be that expensive and you could take the family and you could roam around.”

As someone whose grassroots experience sparked an immediate passion, Fanning argues that people gradually drifted away from racing and the equine in general. She said that a diminishing exposure to animals and agriculture among the general population has, by extension, created a disconnect from racing.

“I’m not sure that I would have ended up in harness racing had a standardbred farm not been down the road from me. […] If people never even get that first exposure to horses, you know, other than you see them in Central Park, or you see them in the circus, or you see them on the rodeo, you’re losing that chance to find that magnetic attraction that a person might have.”

Driver Rick Zeron remains optimistic. The Ottawa native drove his first race in 1975 and moved to Montreal in 1980, where he became the leading driver at Blue Bonnets Raceway in nine of 13 years from 1982 to 1995. Ten years later, Blue Bonnets closed for good.

“At the time when I was a Blue Bonnets, there was no betting on phones, or the lottery, or anything like that. There wasn’t any of that; you had to go to the track to bet the horses,” he said. “No, I didn’t think it would decline. And I’ll go back to saying that it really hasn’t declined in the bet on the wagering – it’s declined (in terms of) the people that aren’t at the track anymore. That’s what’s declined. Did I think that would ever happen? Not in a million years. I never thought that that would happen.”

When Zeron moved again to Toronto in 1995, he found perennial success at Woodbine Racetrack and Mohawk Park, Ontario’s leading circuits. He drove horses to more than $5 million in earnings every year from 2002-2011 and continued to hit seven figures until he scaled back his drives in the late 2010s. The horseman has been successful outside of the sulky too. Zeron has trained more than 2,300 winners, and his horses have brought in more than $34 million.

Though he has lived in Ontario for nearly three decades now, Zeron said he misses two things most about Quebec.

“My fondest memories of being in Montreal are the people and the food,” he said. “My God, the food was so good in Montreal. French cuisine – oh, good Lord Almighty, do I ever miss it. And I’ve been here since 1995, and I still go back to see some of my friends in Montreal. Just to go back and sit down and have a steak with that French sauce that they have on it, or poutines, or the hotdogs that they make – I don’t know what they do, they just make the food incredible. And the people. The people, I found, in Quebec were so nice. So pleasant. (The) people loved horses.”

He said that wagering has not declined much since the heyday of the 70s and 80s, but that the unmissable drop-off has been in attendance.

“They were jam-packed,” he said, remembering the grandstands at Blue Bonnets. “You couldn’t get in. There were just people standing on top of people. That’s how much that there was public going to watch.”

Zeron thinks that a rejuvenation, and the continued existence of harness racing, is inevitable. The second-generation horseman said that the decline is part of a natural cycle that occurs within racing. He said that another star people’s horse, along with increased advertising efforts, will bring people back to the track.

“But now the horse racing, I still believe that is still as strong,” he said. “It’ll dip and dive like the stock market a little bit, but horse racing will always be around. It’ll always be strong. It’ll go weak, it’ll mellow out, and then there’ll be a couple of real big horses that come into the spotlight.

“If there’s a real good world champion horse that’s out there, and WEG – Woodbine Entertainment Group – the people that work in it that do the advertising and promotions, if they promote that horse coming up here and advertise on the TV, and on radio and stuff like that in the newspaper, people will read that and watch it on TV and listen to it on the radio. They’re going to say to their wife, ‘well, listen, sweetheart, why don’t we go watch this horse race? It’s supposed to be a real phenomenal horse.’ So now all of a sudden, your betting goes back up, because there’s a world champion horse that’s out there.”

Industry-wide attendance to racetracks began to fall in the late 1970s. At the same time, the National Basketball Association and National Football League began to explode in popularity in the United States. Commercialized leagues overtook horse racing as the highest-attended sports in 1984 when Major League Baseball took the top spot. Along with the big four leagues, more recently, came something new to gamble on. The remaining question is why numerous forms of entertainment – other sports, especially – flourished as harness racing faltered.

While every racing participant can point to a plethora of individual decisions or inactions, the general consensus seems to be a failure to organize internally and a failure to compete externally.

“The country of France declared a PMU – pari-mutuel union. And they unionized. And they are now – other than maybe Dubai, on their select race days – they have more wagering done than anywhere,” Wolf said. “And all the horsemen, all the breeders, everyone in France, as long as they’re a part of that PMU, they’re doing well, and they’re making money. And granted, (it’s) because they’re unionized, whereas in the United States, every state does its own thing. Every state has its own rules and conditions, and it doesn’t jive with everyone.”

Without that internal structure, Wolf argues, it was difficult for the industry to advocate for itself and coordinate a response to the spectre of new forms of gambling. He said that the industry had to ally with the lottery and the casino and/or better advertise itself to keep bringing new people to the racetrack. It also may have helped to better integrate new technology, including something also often cited as a destructive force: simulcast.

Many in harness racing see simulcast, which allows for off-track and remote wagering, as a factor in the falling attendance numbers. People, they argue, have little incentive to visit the racetrack if they can bet from their phone at home. There is a clear deviation in all-source handle and on-track wagering around the time of the invention of simulcast.

Ryan Clements, an owner, trainer, software developer, and photographer, notes that the large proportion of off-track dollars leave racetracks with less revenue.

“When simulcast wagering first came along, and they were they were taking bets away from the track for the first time ever,” he said. “So, the track operators naturally thought okay, ’95 per cent of my wagering or 99 per cent is still going to happen on the track, and it’s going to be just, you know, the odd bets come in from elsewhere. So what we’ll do is we’ll create a host fee, somewhere between one and five per cent, and what we’ll do is the, the telefeeder who takes the bets can keep all the takeout. And we’ll just take one, two, three, four per cent, whatever our host fee is.’ Now, they never saw coming, that people would be sitting at home betting on their computers.

“And in the COVID era, nobody’s at the track betting. So the track goes from getting the full takeout, to only getting a very small percentage of it. And basically, it’s a crushing business model that stopped the tracks from being able to spend money and made it very hard for them to survive. And yet, they can’t do anything about it, because it’s been an established business model that just has broke their back.”

Clements’ racing experience is unusual. Like a large portion of horsepeople, he was born into the sport – his father, Daniel, owns, trains, and drives harness horses. Clements, though, started on a different path and went to university. In second year, he launched Online Harness Owner, a fractional ownership business that allowed customers to buy shares in racehorses. It thrived, and he soon dropped out of school to pursue it full-time. The now 35-year-old Uxbridge native is among a minority demographic of young people in the sport, and has studied coding, among other technology-based skills. Though he since shut down Online Harness Owner, Clements has started other businesses. He started Bad Jump Games, which has produced five mobile horse racing video games. He became the track photographer at Hanover Raceway, and channeled his photography work into Thebit.ca, a website he developed to host digital versions of his shots for sale but now is transitioning into a one-stop shop for racing info.

Clements, having worked in other industries before returning to harness racing, casts a blameful eye at the way the sport has negotiated for itself.

“It’s in every facet of it, like, you pick out a certain piece of it, and it doesn’t make any sense,” he said. “Like you pick out the video, and the astronomical rates that they’re paying Roberts (Communications) to distribute their signal, when YouTube will distribute it free in HD to the world. They’re operating at the time when Roberts used to have satellite dishes at the track and have a kind of staff there, and the cost was very high to do these things. Of course, now, today with widespread internet, it shouldn’t cost anything. And yet they’re still paying these, like exorbitant rates, because that’s where they’re stuck.”

Peter Gross, a veteran Toronto journalist with a lifelong interest in horse racing, said the racing industry has failed to expand to new demographics, leaving a majority of older men.

“They haven’t so much done a poor job of attracting young people. But they need to put enormous resources into bringing young people to the track,” he said. “Because I’m 71. And I represent the constituency that really loves horse racing and understands the racing form – that knows the trainers and the owners, and the jockeys, you know, for years and years and years. And that’s why I play the races. And as the crowd gets younger and younger, as people get younger and younger, they have less interest in the races. And when I die, when your dad dies, there’s just not going to be an audience for you. And it’s mostly men. […] Horse racing is the only professional sport in which women regularly beat the men on a level playing field. So women are half the audience, right? So I would make a series of ads or promotions telling people that horse racing is a sport in which women are half the equation.

“I would say 90 to 95 per cent of the money bet at the track is bet by men. I could be wrong, but most obviously most of it is bet by men.”

Gross’s father introduced him to horse racing at an early age, and he’s been involved since. Gross is best-known for his roles on CityPulse and 680 News, but the 71-year-old has maintained his love for thoroughbreds and standardbreds through the years. When he came into money in 2007, he pursued his dream of starting his own racing paper. He began publishing the Down the Stretch newspaper later that year, and, in 2020, created the Down the Stretch Podcast. Both focus on horse racing in Canada.

Though he has gripes with several issues within the pari-mutuel system, Gross identified the major problem as the sport has doing little to market its own business model.

“When you go to the track, the product is horse racing,” he said. “But the business model – the only way aside from food and beverage – only way that racetracks make money is the pari-mutuels. The business is pari-mutuels. Have you ever seen a commercial or an ad that says ‘come bet the horses, you get a better buck for your dollar, come bet pari-mutuels, it’s better than the lottery, come bet pari-mutuels, it’s the fairest way to gamble?’ They don’t. it’s the only product in the world that doesn’t spend one dollar promoting their business model.”

Clements holds the view that an influx of new gambling and entertainment options tore the market share and relevance away from racing. Along with a restrictive infrastructure, Clements said that the sport failed to adapt to a changing, increasingly instant world. He argues that harness racing did not innovate its wagering side enough to compete with casinos. But he thinks that there has been no effort to make the product entertaining.

“I believe the sport has gotten incredibly boring,” he said. “It used to be like: people followed this horse, there was celebrities and personalities in the harness racing world. And I honestly haven’t been a fan of a horse since Admirals Express. It’s just not there anymore. Like we get to see these horses race such a short period of time. And it’s like, yeah, the odd one will capture my attention. But for the most part, the way that harness racing has gone, is it would be like, it’d be like if the NFL only had the regular season. And there was no Super Bowl and there’s no playoffs. […] There’s no grouping of horses so I don’t get to see rivalries form. I don’t get to see any storylines. It’s just another race.”

Clements clarified that horse racing itself can be exciting, and that the horses and the action can draw people in. However, he believes the current presentation of the sport is not able to attract or retain a constant stream of followers.

Wolf argued the main reason for a growing attitude for disinterest was oversaturation. While the NFL has a 16-game regular season and basketball has 82, he said, racetracks in total have hundreds of race dates per year.

“(In the) ’60s and ’70s, nobody raced almost year-round, like the tracks do now. And I think that was a big part. I think they flooded the market because they owned it. And now that they didn’t own it anymore, they continued to flood it, and it became like I can go to the races any day. […] And Freehold didn’t race that much and, you know, Brandywine and Liberty Bell, they never fought against each other – one would close and the other would open, so they would have a circuit. And we’d go for one, and people would follow that. But then, they got greedy, and they fought against each other. And that destroyed them.”

With so many contrasting ideas about the reasons for racing’s downfall come a range of opinions about what should have happened. Below are clips of each source explaining what they, as the hypothetical monarch of harness racing, would have done in the 1970s to avert the decline. Zeron instead discusses how the racing industry should stimulate the growth of the fanbase.

So where did everybody go? The answer seems to be “anywhere but here.” Yet still, harness racing in North America pulls in around $1.5 billion a year. The sport’s biggest nights do draw crowds reminiscent of the 1970s. There is clearly still hunger for racing. The question of the future will be how to harness it.

USA

USA Canada

Canada Australia

Australia New Zealand

New Zealand Europe

Europe UK / IRE

UK / IRE